| Index of articles from the Blog |

| Animals |

| Anthropology & Archaeology |

| Art & Cinema |

| Biography |

| Books & Authors |

| Culture |

| Economics |

| Environment |

| Fiction & Poetry |

| History |

| Humor |

| Justice |

| Philosophy |

| Photography |

| Politics |

| Religion |

| Science |

| Travel |

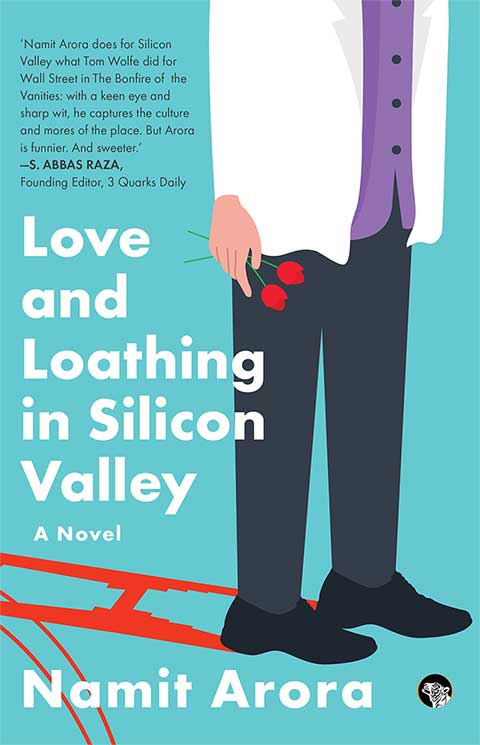

Books by

Books by

|

By Namit Arora | Apr 2023 | Comments

On Doordarshan's 'documentary film' on Indian heritage. First published in The Wire.

For every nation, the past plays a pivotal role in creating the ‘imagined community’. Stories about a nation’s past, including stories about its origins, shape its members’ collective memory and identity, creating a ‘national consciousness’. Certain historical moments, figures, and symbols are elevated to a position of great importance within the imagined community. These help fortify the ideas, beliefs, and values that are said to underpin a ‘national identity’. This is also why nations fixate on history curriculums so much. History can of course be approached in many ways. There is no perfectly objective way of doing so, but some approaches are decidedly better than others. At one end of the spectrum are academic scholars in diverse communities, who lean on the latest evidence, make reasoned interpretations, and openly debate one another in peer-reviewed forums to evolve our knowledge of the past. At the other end are chauvinists who interpret the past with the objective of favoring a particular group, often willfully ignoring or fabricating evidence. Their unashamedly partisan approach is led by a hegemonic sense of identity. The goal is to bolster pride, even supremacist pride, in a subgroup. If that subgroup happens to be the majority, it produces majoritarian politics at the expense of minorities. History seen from such insular points of view tends to inflate the fears, resentments, and tribal loyalties among its target audience, thereby exacerbating civil and communal strife. India is now drowning in the latter kind of historical storytelling. A recent example is a Hindi ‘documentary’film, clumsily titled Dharohar Bharat Ki Punarutthaan Ki Kahani (‘The Story of the Resurgence of Indian Heritage’). It recently aired in two 30-minute episodes on Doordarshan (whose charade of autonomy finally collapsed when it agreed to receive all its news from an RSS affiliated agency). The film begins with some reasonable questions: Where did our ancestors come from? Where do the roots of our culture and civilization begin? Shouldn’t a proud nation preserve the stories and heritage of its past? But the narrative is promptly derailed by partisan rhetoric: Who is taking up the burden of restoring to our heritage the respect it deserves? Who is preserving and rejuvenating it for future generations? None other than our own Prime Minister Narendra Modi ji! From there, the film descends steeply into travesty, as it reveals its skewed view of the dharohar (heritage) that’s worth preserving: Hindu pilgrimage sites, and memorials related to anti-colonial leaders favored by Hindu nationalists. The film begins its account of India’s past with a story from Satya Yuga, when Shiva’s anger at Brahma and Vishnu lights up twelve spots on earth, each with a Shiva Lingam. The filmmakers simply present this as historical fact without any dates or context. This recurs throughout the film. It’s one thing for a village priest to relate things this way, quite another for the narrator of a prime-time documentary on national public television. Worse, one suspects that the filmmakers’ disinterest in separating fact from fiction isn’t accidental but deliberate. Indeed, the intellectually curious will find in the film practically no historical insights about Indian heritage. Let me share some examples. The first and the foremost of the twelve spots mentioned above is apparently Somnath temple. The filmmakers remind us twice that it was plundered and destroyed often. That the film begins with this site is revealing enough. Its desecration by Mahmud of Ghazni in 1026 CE is central to Hindu Nationalists’ animus against Muslims, and claims of the Hindu community’s lingering social trauma and memories of humiliation. But of course they never tell us that Hindu historical sources of that era are silent about this raid. Wouldn’t Hindu chroniclers have recorded and remembered such a painful event? Scholars have examined and offered reasons for how this event was evidently soon forgotten. Eight centuries later, its historicity was only discovered in dusty Turko-Persian sources by British Orientalists in mid-nineteenth century—and through them by modern Hindus. The alleged thousand years of memory and ‘social trauma’ was then invented and weaponized by modern Hindu nationalists for their partisan ends and emerging identity politics. Inheriting that legacy, this film, too, glibly claims that the revamped Somnath temple complex represents ‘our growing self-confidence and reawakened spirit’. The film then jumps across yugas to the founding of the Mahakaal temple in Ujjain. According to a Puranic myth, Shiva had appeared here to kill an asura. But the film presents this too as historical fact. We see sumptuous drone footage of the upgraded sites: Somnath temple, Mahakaal temple, Pavagarh temple, Kashi Vishwanath temple, Kedarnath temple, and the upcoming Ram temple in Ayodhya. Each is discussed with devotional awe and cloying piety. We’re told that perhaps God himself commanded that the foundation stone of the Ram temple be laid by none other than PM Modi ji—echoing Hindu kings establishing their divine right to rule—a task he carried out on national TV in full religious regalia in August 2020. The segment on freedom fighters lovingly lingers on VD Savarkar, and Modi is shown offering prayers to his likeness at Cellular Jail on Andaman Island. The film takes us to Patel’s Statue of Unity and Subhas Bose’s new statue by India Gate in Delhi. While Savarkar, the godfather of Hindutva ideology, oddly dominates the many montages of freedom fighters who won us our freedom, Nehru is entirely missing—a comic, childish, and sinister move, all rolled into one. This erasure is akin to the Indian government’s recent move to wipe all Mughals from school textbooks. It’s also reminiscent of Joseph Stalin vindictively erasing his ideological enemies from historical photographs. Gandhi’s stature with Hindu nationalists has declined over the decades, but he still remains un-erasable, for now. In this film, he plays second fiddle to Savarkar. We hear of plans to turn Sabarmati Ashram into a ‘world class’ attraction (a favorite term of the filmmakers). This means it will likely lose forever the austere realism of Gandhi’s former home. Likewise, we learn of plans to turn five places associated with Ambedkar into hi-tech teerths, or pilgrimage sites. There is no mention of caste or untouchability, only his long struggle for ‘deprived classes’. The host, Kamiya Jani, continuing her relentlessly bland and whitewashed commentary in designer outfits, tells us that Ambedkar is a symbol of equality and was very fond of reading and writing. You don’t say! We do not learn from her that he called Hinduism a disease and exited it publicly to embrace Buddhism. But even then, the proud Hindus behind this film can’t ignore him. A little matter of electoral calculus, eh? We witness the botched-up restoration job at Jallianwala Bagh that was widely criticized in 2021. We watch Modi inaugurating a national war memorial in Delhi. A saccharine patriotism suffuses the film, evoking the last refuge of scoundrels. Not a single heritage or religious site associated with Muslims appears in this film. Not even Sufi shrines, such as Ajmer Sharif or Nizamuddin Auliya, that have crossover appeal for Hindus. No Christian sites. No Buddhist sites. Not even the wrong kinds of Hindu sites—those with non-living temples or an excess of genitals on display. Are such heritage sites not worthy of investment? ‘No’ seems to be the implied answer in the film. It manifestly sees India as a pious Hindu nation. It brazenly shows the officially secular Indian state touting its vigorous investment in Hindu religion but not in other faiths. Upper-caste Hindu views of India’s past overwhelm all others. It’s amply clear what ‘imagined community’ and aspirational nation the filmmakers are reaching for. This film about Modi ‘rejuvenating’ the nation’s long-neglected heritage is also deceptive in other ways. It comes months after his own Union Minister of Culture revealed in Parliament that 50 out of India’s 3,693 centrally protected monuments of national importance have gone missing. Yes, missing, as in untraceable! A disproportionate number of these are non-Hindu sites. A further 42 monuments were earlier deemed untraceable but have now been technically located, though the ministry is silent about their found state. Budgetary restrictions have meant that only 248 of these 3,693 monuments of national importance have security guards. The rest are fair game for vandalism and urban development led by unscrupulous builders and public officials. So much for protecting the nation’s dharohar! The film’s unabashed lack of equity, historical sense, or scientific temper also exposes its actual genre: propaganda and cult worship of the Dear Leader, in the tradition of Leni Riefenstahl. Dear Leader appears frequently, inaugurates, utters social and religious platitudes, does puja, and takes pride in the Disneyfication of various sites. Fawning, gushing visitor testimonies abound. He thinks his Central Vista vanity project and the renaming of Raj Path to Kartavya Path are acts of decolonisation, even as he inhabits that quintessentially colonial ideology of divide and rule. In conclusion, dear reader, save yourself from an hour of unremitting odium and tedium. Watch this film only if you’re an anthropologist, a masochist, or a true blue bhakt. This sectarian film is in fact a symptom of the larger malaise that’s afflicting India and darkening its horizons. Benedict Anderson knew that of the many ways of forging an ‘imagined community’, the more salutary ones rely on secular identities, shared history, civic values, and inclusive social practices. Whereas relying on racial or religious identities to make a nation only produces strife-ridden polities. Yet experiments of the latter kind abound, including neighboring Pakistan and Sri Lanka—and now increasingly, also India. Will enough Indians change course and avoid the abyss? ___________________________ More writing by Namit Arora? |

Designed in collaboration with Vitalect, Inc. All rights reserved. |

|