| Index of articles from the Blog |

| Animals |

| Anthropology & Archaeology |

| Art & Cinema |

| Biography |

| Books & Authors |

| Culture |

| Economics |

| Environment |

| Fiction & Poetry |

| History |

| Humor |

| Justice |

| Philosophy |

| Photography |

| Politics |

| Religion |

| Science |

| Travel |

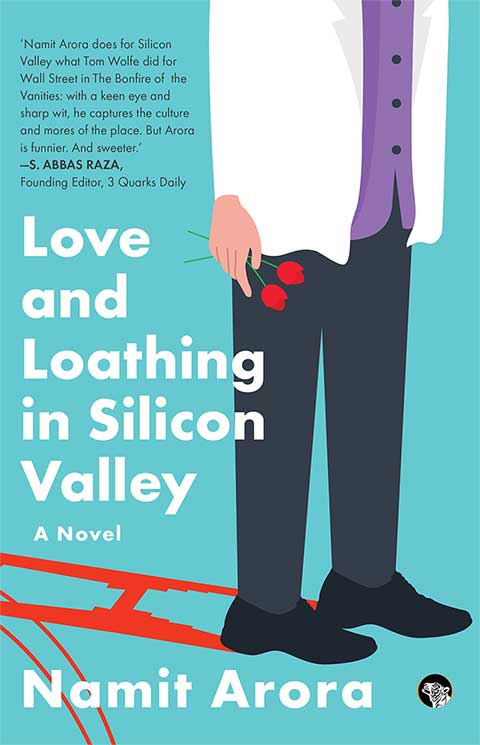

Books by

Books by

|

On the Indian Knowledge Systems Calendar from IIT Kharagpur

By Namit Arora | Jan 2021 | Comments

(This article also appeared in Raiot.)

Early India had many solid achievements in advancing knowledge but this calendar’s authors miss loads of them while twisting others into convoluted descriptions laced with Sanskrit jargon. For instance, they ignore the Harappans entirely—their fine urban planning, precision weights and measures, hydraulic engineering, the first indoor toilets in the world, a relatively egalitarian society with no standing armies or temples. Instead, they begin with legendary Vedic sages. It’s as though they can’t—or willfully do not wish to—acknowledge that the roots of any knowledge system could possibly lie earlier and outside of the holy Vedas. They also repeat the absurd claim that Sanskrit is ‘the root of the entire Indo-Aryan branch in Asia and systems of European languages.’ No, it’s not. Sanskrit is just another branch of the family, like Persian and Greek. This false claim also reveals their foundational belief that Aryans did not migrate into the Subcontinent, that Vedic people were indigenous to this land and carried Sanskrit westward. There never was any scholarly justification for this belief, which was driven by ignoble motives: the creators of the Vedas have to be ‘made’ primordially indigenous to promote Hindu pride and ‘faith and fatherland’ nationalism—and to render Islam and Christianity ‘invader’ religions. But the fact is that, to the extent that the Rig Veda, Sanskrit, and priestly fire rituals are seen as foundational to Hinduism, Hinduism too is an ‘invader’ religion that arrived with the Aryans from Central Asia.

Throughout the calendar, the authors display their penchant for authority over explanation—an approach that’s anathema to science—by relying on adulatory quotes and photos of famous white people, including many born in the 18–19th centuries, when little was known about India’s past, of which these men knew further little. As with Voltaire and Mark Twain, these men often praised things Indian for their own varied reasons; for instance, they extrapolated from fragmentary tidbits about India to fight another battle: combatting their fellow countrymen drunk on the presumed supremacy of Christianity and European civilization and its destiny to rule the world. The calendar abounds in such fakery, alongside half-truths and not-even-wrong claims. Indeed, their entire approach is ludicrous. Mind you, this may seem like a product of ‘WhatsApp University,’ but it’s actually the joint work of IIT Kharagpur’s Nehru Museum of Science and Technology and its new Center of Excellence for Indian Knowledge Systems, which was announced by India’s Hindu nationalist government in November 2020. The Center was launched with a three-day webinar titled—wait for it—Bharata Tirtha (‘Indian Pilgrimage’). India’s cabinet minister of education attended this tirtha. ‘We lacked nothing—in knowledge, science, talent, vision, mission, hard work,’ he asserted, ‘yet we suffered hundreds of years of painful slavery. Generations today must learn how our illustrious heritage was destroyed’ (my translation from his Hindi). The new Center, he said, symbolizes the ‘rising soul of Vishwaguru India’. The faculty attached to the Museum and the Center, some of whom spoke at the webinar, seemed to lack disciplinary training in the history of science. One professor, nauseatingly unctuous towards ministerial authority, eulogized Syama Prasad Mukherjee, founder of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, precursor to the BJP, and lavishly praised an RSS stalwart and invited speaker for his crusade to ‘correct’ our history textbooks. (This stalwart, an ‘educator’ and proponent of ‘holistic education’, soon clarified that solutions to most problems already exist in our holy shastras; we just need to extract and integrate them in our curriculum.) The same professor also displayed a cloying parochialism as he voiced highlights from this calendar, presented via slides containing even more howlers: Not just zero and the decimal system, even ‘the birth of mathematics and algorithm’ occurred in India. Pythagoras of Samos, said another slide, trekked from Greece to the banks of the Ganga in sixth century BCE to learn the geometry he’s famous for! I couldn’t decide whether to laugh or cry. Clearly, this calendar isn’t the work of scholars moved by scientific temper and its ideals of dispassionate analysis and judicious skepticism. The sensibilities that animate it diminish one’s trust in their entire endeavor, so that even the few claims that are true, or seem plausible, feel tainted in their hands. It resembles classic overcompensation by a people with an inferiority complex. It reflects bad pedagogy too. All told, the calendar is unwittingly a prime illustration of why premier Indian institutes still have a long way to go before they catch up with their leading global counterparts. _________________________ Namit Arora is the author of Indians: A Brief History of a Civilization (Penguin India, Jan 2021) |

Designed in collaboration with Vitalect, Inc. All rights reserved. |

|