| Index of articles from the Blog |

| Animals |

| Anthropology & Archaeology |

| Art & Cinema |

| Biography |

| Books & Authors |

| Culture |

| Economics |

| Environment |

| Fiction & Poetry |

| History |

| Humor |

| Justice |

| Philosophy |

| Photography |

| Politics |

| Religion |

| Science |

| Travel |

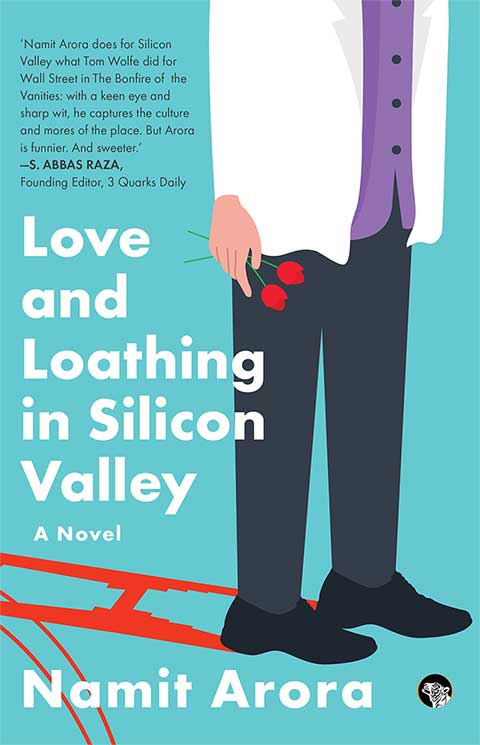

Books by

Books by

|

By Namit Arora | Dec 2006 | Comments

(A version of this essay appeared in The Avatar Review.)

Spirituality is cool these days. Its warm and fuzzy aura now appeals to more and more people in the West. Online dating sites abound with claims of being "spiritual but not religious". Interest in eastern beliefs and native Indian practices has never been higher. Many now instinctively accord a sense of "spiritual wisdom" to ancient traditions. Self-help aisles in bookstores keep growing and routinely address a "spiritual void" many perceive in their lives. Yet most people interested in spirituality, when asked, would be hard pressed to come up with what it means to be spiritual. Many would equate it with less or more progressive versions of their traditional faith, incorporating a subset of its ideas, symbols, and rituals; some might define it as a syncretic mix of multiple faiths; others may think of it as a non-denominational mystical feeling and reverence for a force larger than themselves, such as nature. I have my own idea of spirituality, of course,

and I consider some people more spiritual than others. Yet I rarely find

an idea of spirituality that I wholly admire. Last year, for instance, the

president of World Pantheism,

which claims lots of luminaries on its roster, wrote to me to request use

of some of my photos, "We are completely naturalistic and nature-oriented—our views go under several other names such as religious naturalism,

naturalistic spirituality, eco-humanism, etc." In my affirmative reply,

I also noted my own thoughts about nature reverence: As an aside: Immensely progressive as your World Pantheistic Movement belief statement is, I must admit that I personally have trouble according reverence to nature. I feel immense wonder, but no reverence. Nature to me is brutal and violent. All available evidence suggests that nothing in nature cares about me—I am a pawn in its pointless (as far as we can tell) bloody game. So why should I waste my reverence on it? I offer below my provisional thoughts on what being spiritual means to me. Readers are invited to react or post their own views. To me spirituality is inseparable from reason. Without a restless energy that seeks self-knowledge—leading to a higher self-awareness—there is no spirituality. A belief in god is an obstacle to my idea of spirituality; it may have therapeutic value but I consider it superstition, rooted in fear and ignorance. A somewhat stronger expression of my own view on god—but far more confrontational that I desire to be—was put forth by Periyar Ramasami, a social reformer in south India: "He who created god was a fool, he who spreads his name is a scoundrel, and he who worships him is a barbarian." To be spiritual is to attend to your spirit—the sensibility that evokes joy and sorrow, pleasure and pain, empathy and remorse. To be spiritual is to be compassionate without discounting (or overestimating) the value of knowledge and detachment. Spirituality evades the incurious, and the complacent, and those who do not doubt, and those who have the final answers, and those who complain too much. Those who don't have frequent raging debates in their heads cannot be spiritual. Wonder is a prerequisite, as are personal responsibility and attention to cause and effect. Some years ago, I came across a great metaphor

for the human psyche: the zoo. Imagine a zoo with a zookeeper and lots of

animals, wild and domestic, ferocious and meek, whose well-being depends

on the zookeeper's knowledge of their unique traits. If he slouches off,

the animals might suffer, or might turn on each other, and the overall

health of the zoo suffers. The animals represent the subterranean forces

within us—the source of our feelings, passions, creativity. The zookeeper

represents the rational faculty, drawn to analysis, order, classification.

Together they make up our psyche (or soul). The zookeeper may study the

animals but not tamper with their natures to avoid unpleasant side

effects. Also part of his job is to toss lobes of meat to the leopard,

feed bananas to the monkeys, and make numerous other arrangements—all for

the health of the zoo. One can build the metaphor further. For example,

the animals inhabit constrained spaces, much like the effect culture, or

other social conditioning, has on our psyche. To be spiritual is to try and understand our inner zoo. The spiritual person aspires to be ruled by an analytical faculty that knows its own limits, knows when to humbly step aside and let the non-analytical faculties do their work, and listen to them soberly, vigilantly. An alert awareness of our inner zoo is the hallmark of the spiritual. |

Designed in collaboration with Vitalect, Inc. All rights reserved. |

|